The Telephone Game enables participants to experience literature independent of the written text via this old children’s game. A participant starts reading a story to another participant, and this goes on until the last participant’s story is put into writing. The last author, who imagines the narrative only through oral transmission, re-creates the story by staying loyal to what they’ve heard. Finalized with the comparison of the original story with the last one, the workshop examines the differences between oral and written narratives.

A Brief Summary: Do What I Tell You to, Not What I Write

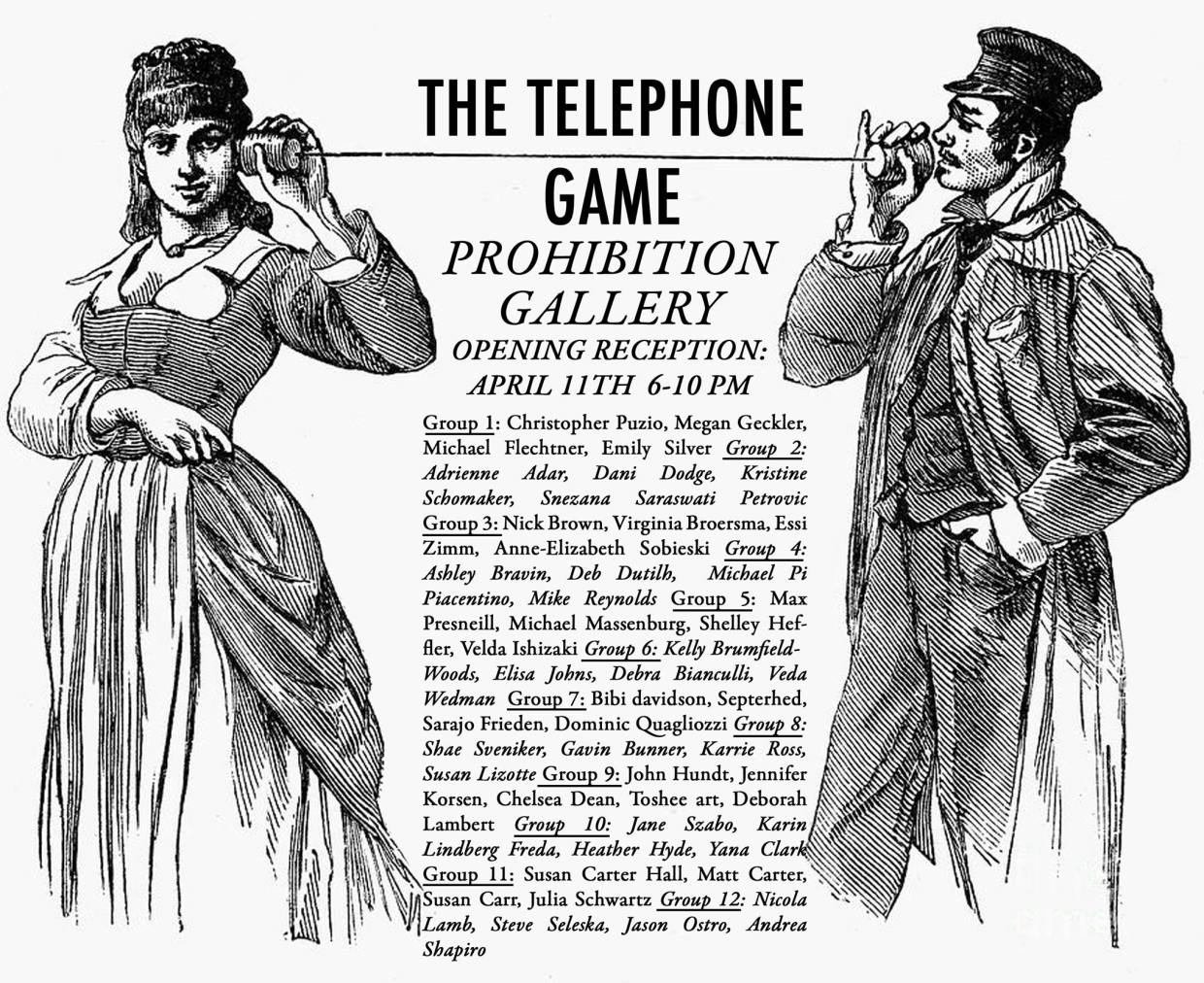

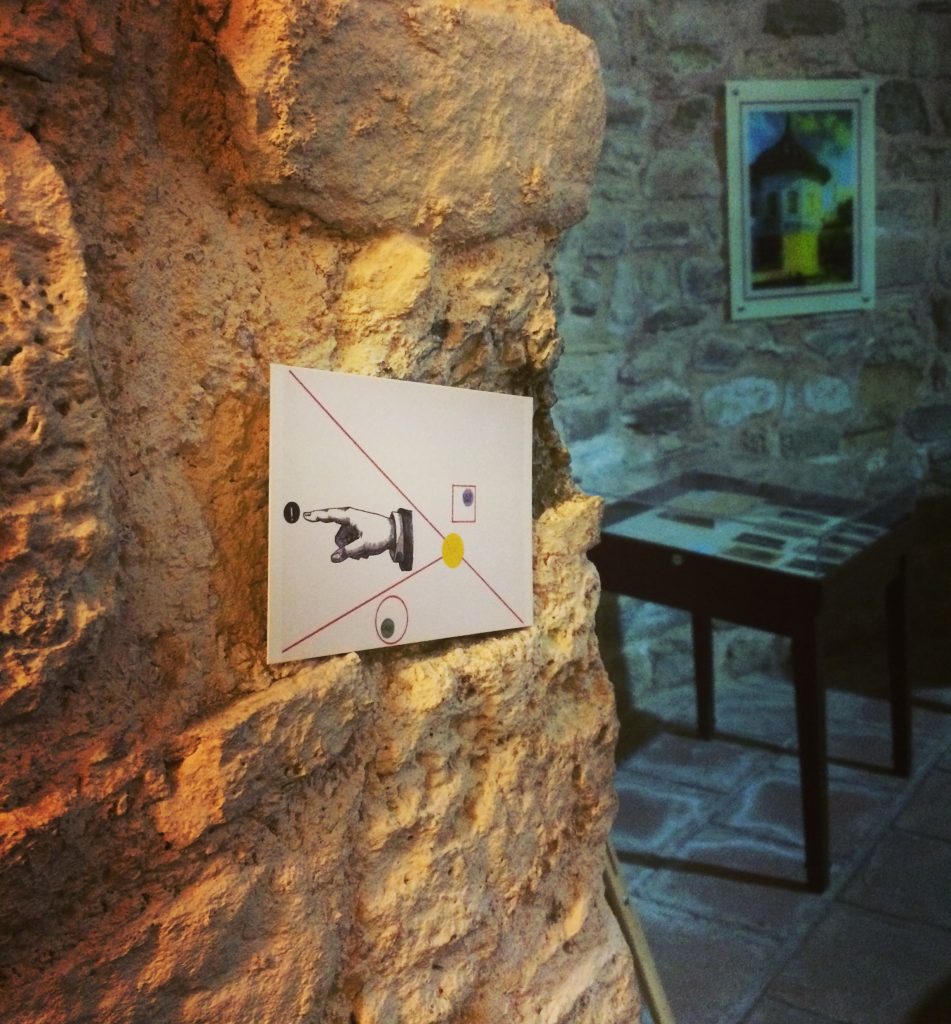

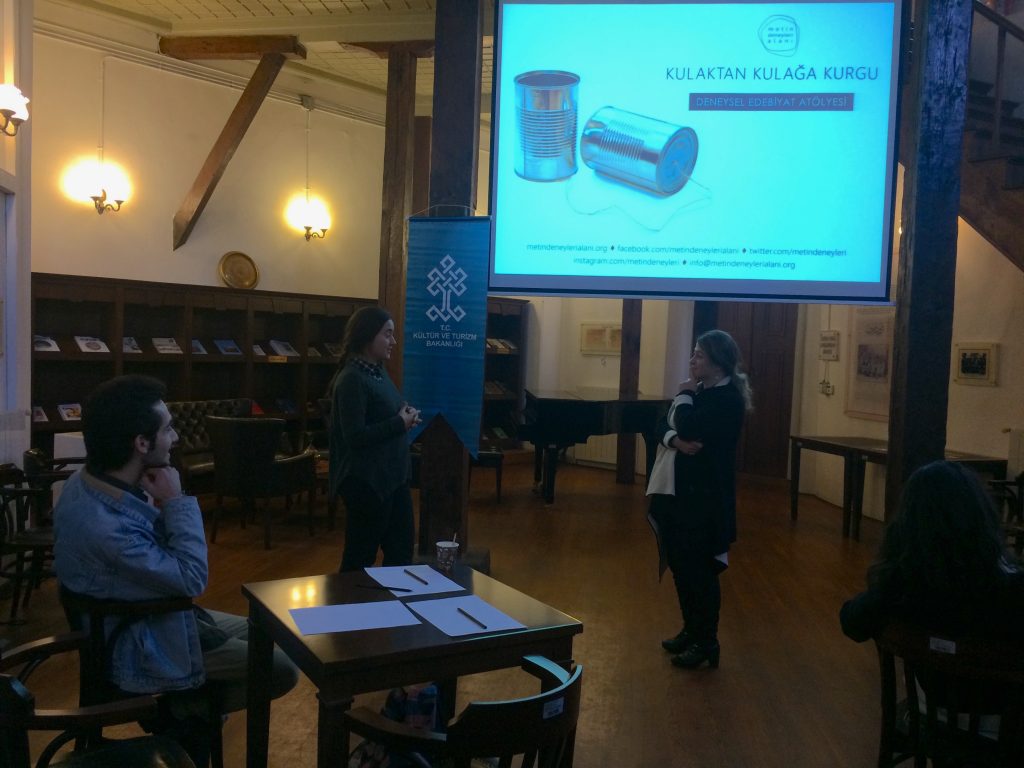

We came together with experimental “player-authors” at Ahmet Hamdi Tanpınar Literature Museum Library a few days back. The building where we held “The Telephone Game” on December 17, was built as the Procession Mansion and reserved for the use of Fine Arts Association during the first years of the Republic, then to become a literature center, frequented by Tanpınar himself. The stories circulated not on paper, but around the air in the stone room.

We held the workshop in the wide hall, situated between the small room where old literary magazines –including Servet-i Fünûn, Yaprak and Varlık– were on display, and the dungeon, where the prisoners sentenced to death were kept. Though the coldness of the dungeon seeped into the stories, the piano in the hall was enough to melt the ice.

Unlike our previous workshops, we focused on oral narrative at “The Telephone Game”. The workshop was based on taking the three short stories out of the written format, orally transmitting them among five people as in the children’s game, and the last person trying to put it into the written format once again. The game was repeated with three groups, in which actor-authors first observed the others playing the game deriving from a written story and then switched places with them.

The focus of the workshop set off from the idea to transform the texts written by a single author into a transmission that proceeded like a daily storytelling experience. We examined what the oral narration of a story adds to/leaves out of the original.

Having listened to the story from another narrator, the participants hadn’t read the story yet – unlike the observers. Therefore, all of their conception of the story was based on what the narrator told them. The listener then relayed what she remembered from the narrative and it went on. At the end of the game, the fifth participant put the narrative into writing. They paid attention to the story’s narrative as well as its atmosphere, style and the author’s manner of writing.

Just as an actually experienced narrative loses some of its elements or gains new additional stories when orally transmitted, the narrated stories at the workshop took new shapes. We have witnessed how a recorded narrative that’s regarded original can transform into other things when transmitted from one person to next via oral narration.

For the workshop, we chose stories written by Ali Teoman, Donald Barthelme and Sine Ergün, each of which turned into a fantastic fiction, a brand-new product, or an expression. Since each narrator was also a player-author, when she felt that there was something left out in the story she was being told, she filled this blank with her imagination. This being the case, the fiction created with this game based on oral narration was shaped according to the narrator’s personality, manner, memory, imagination and mood.

Just as new fiction is produced with each narrative within the society, these written texts, originally written by a single author, were transformed into a collective story, orally fictionalized by four to five authors at once, overlapping at times or expanding towards eternity like the free pulse of imagination in others.

There was an unexpected variable at the workshop as well. Not all narrators acted the same way when telling a short story in front of newly-met observers. Some narratives took long while others lasted shorter. Having caused serious deviations from the story’s essence, this situation increased the responsibility of the actor-author who was to put the story into writing at the end of the game. For instance, the story “Savaş Sonu” by Ali Teoman lost most of its core elements by the time it reached the last player, diminished to mere two sentences at the end of the game. Player-author created a brand-new story with her imagination just with these two sentences.

Or the game with the story “Kamyon Şoförleri” by Sine Ergün ended with the last player-author writing a fictionalized story about a Galactic Truck Drivers’ Association:

“Just as every year, the Galactic Truck Drivers’ Federation gathered during the first week of April. The council would discuss the familiar and simple issues left unsolved in the previous years in addition to the problem of new drivers undertaking easy work to go short distance.”

Some participants attempted to deliberately disrupt the narrative – just as the spirit of the workshop allowed them:

“Mr. T was both the founding member and the principal of the long-established R. School. Being the principal of one of the city’s leading establishments with its crowded student population and teachers known for their discipline, made him a stern and a bit haughty.”

At this point, we realized a significant similarity between written narrative and oral narrative. The same way a book’s narrative is transmitted from a single author to a single reader, the oral narrative of the game took place from one narrator to one listener. It was true that there were many curious observers present but no one could interfere with the game itself. There was no proof that would point out or prove that the oral narrative that was transmitted from one person to another was different from the original narrative. Just as the necessity for a reader to accept the author’s universe in order to be a part of her reality, all the listeners could do was to accept the fiction told by the narrator. Nevertheless, just as a reader could while reading a book, there were also some listeners who preferred to create new fiction with their own imagination.

Another focal point of the workshop was the difference of creative process between oral narrative and written narrative. The creative process of oral narrative was utterly different from that of written narrative. While the narrative might be simple, short and carefree sentences in oral narrative, putting it into writing implied a whole other creative process.

During the transformation from oral narrative to written narrative, everyone quickly recovered from the pleasant gossip session present a few minutes before. While everyone was fictionalizing a story in a collective and entertaining way a short while back, now it was in the hands of a single author – this personal action was supposed to adopt its familiar seriousness. (Though they were simultaneously watching the writing process on the screen, they chose not to interfere.) The narrative, which, as we observed, loved to jump around was replaced by regular sentences, erased and rewritten, stories with a name and adjectives that abandoned hiding and came out to play.

We had a great time with fellow fans of experimental literature at this venue named after Tanpınar. Aiming to examine the transformation from oral to written narrative and the differences between their creative processes, we learned something far more important: As long as the author is a player-author, she can push a little further and create a brand-new narrative deriving from merely three-or-four-sentence-long oral narratives.

Ahmet Hamdi Tanpınar Museum, Istanbul, 2016